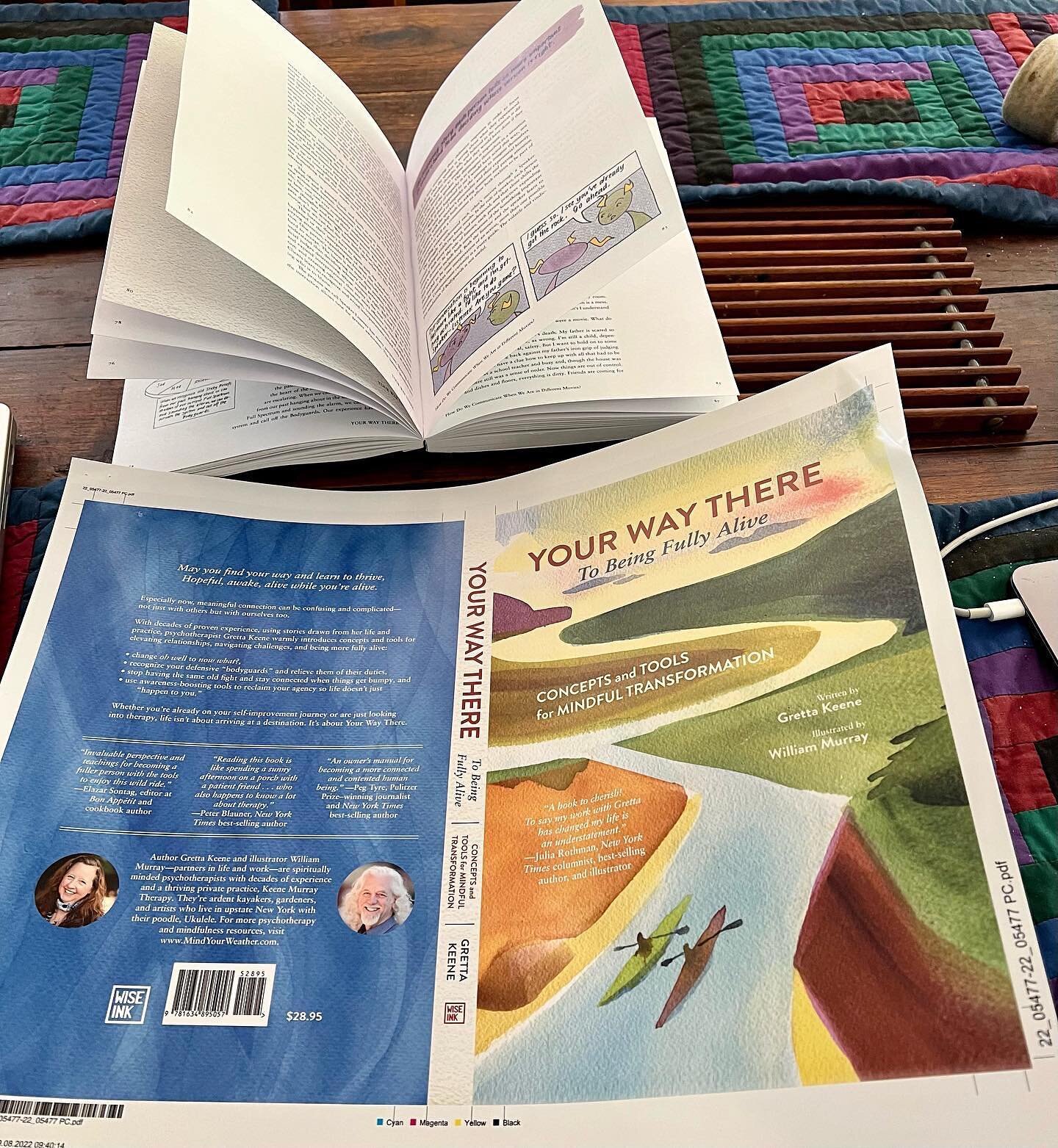

by Gretta Keene from her forthcoming book, A Practical Guide to Being Human, with illustrations by Bill Murray

That morning, land was far away and the water, deep. Wind was whipping up peaks as ominous dark swallowed pale sky. Thunder rumbled. Guiding my slim, spring-green kayak into the four-foot waves of Lake Champlain reminded me of days as a young teen diving into hurricane surf. Scary? Yes, but doable. I was brave. Bill was up ahead in his red kayak. His curly, white mane streamed out from under his floppy hat. We had spent the night camping on an island. Other campers had warned us of the approaching storm and told tales of the treacherous lake. But we had stayed, and now we had to get back. We had no choice. We couldn’t be late for my elder daughter’s engagement party. Better to face an actual storm rather than an emotional one.

The week before, I dubbed my gleaming, newly purchased kayak, “Greenie.” Humans turn objects into symbols by naming them and connecting them to an idea or an object that had symbolic weight in the past. “Greenie” was a subtle reference to “Bluebird,” my childhood bike, vehicle to freedom and adventure. Kayaking was a recent passion, a symbolic “yes!” to feeling strong and capable, choosing to seize life rather than retreat into the limitations of sickness and old age. Bill and I are not ancient humans but since the amount of years we can possibly live is less than the years that are behind us, we are not exactly “middle-aged” humans. We are experienced humans. That day, we were not experienced kayakers.

As a therapist I often use the metaphor of “heading into the waves” as a way to encourage my clients to go towards what is painful and consider other interpretations and responses rather than react with one of The Big Three, deeply embedded defenses: Fight, Flight or Freeze. I know how to touch the tender, terrifying places, how to dive into the high waves of hurt and trauma. I understand the healing that happens when those emotional waves are faced. Unfortunately, confronting high waves was the opposite of what I needed to do. Where we were headed on Lake Champlain was in the same direction the waves were headed, which meant I had to maneuver the seventy-pound piece of Kevlar so that the waves would first hit the side and then come from behind, surprising me with every lift. Every fiber in my being told me, “Not safe!”

“You have to turn!” Bill yelled.

“I can’t!” I wailed. In the grip of fear I chose “flight,” avoiding what I didn’t want to face, and “freeze,” beginning to numb and shut down. All the paddling techniques I had learned in lessons seemed vanished from my brain. I was in what Bill and I refer to as an “activated state.”

My mind became flooded with images of all the terrible things that would happen if I turned my boat. I imagined waves whacking the back of my kayak, dumping me into the churning, deep, cold water. The headlines would read, “Grandma Capsizes in Kayak and Drowns!” The subhead would reveal, “Husband watches, unable to save her.” I envisioned Bill calling the kids, family and friends to tell them the tragic news. How awful to cause such a mess. My daughters would never forgive me.

“It was her own fault!” others would cluck. “Gretta was never athletic. Just like her crippled mother. She should have stuck with crocheting.” Images of my failure in childhood sports played like a cheesy TV-movie montage. My identity was still attached to the gawky girl who couldn’t catch or hit the ball, who no one wanted on their team. “How could I be so stupid as to think I could kayak in a big lake?” My body further stiffened in response to my inner, damning judgment.

Fear had pushed the alarm and activated my unhelpful beliefs about my athletic inadequacy. My defenses, those loyal, hyper-vigilant Bodyguards, seemed to shout in my brain. “Stay with what you know!” they yelled. “Keep the waves in front! Then you’ll be in control, safe.” A sneakier Bodyguard whispered, “Be helpless. Then you’ll get saved. Someone else will take care of you.”

Bill, suddenly much farther away, called again: “Gretta! There is nowhere to land in that direction! You have to turn!”

Greenie and I lifted and slapped against the water, lifted and slapped, lifted and slapped. A gust of wind had yanked my hat off my head. The hat strings tugged at my throat. My face and hair were wet from the spray. I resisted the urge to cry. Where was the fast forward button that would instantly change the scene to safe and cozy, Bill and me cuddled in front of a toasty fire?

The only way to that future moment is from the present moment.

The only one who could get me there was me. I struggled to remember what I knew when I wasn’t brainwashed by judgment and fear. I didn’t need to let old Bodyguards run the show. I could choose a more effective reaction. I could choose to –

“Breathe!”

I’d been holding my breath, grabbing quick shallow gulps of air. I took three slow, deep abdominal breaths and with a long exhale I imagined myself releasing the fear. I came back into my body, out of the stories of past and future. I would trust Greenie and myself, stroke-by-stroke, to make it home. Concentrating on the physical sensations of the paddle in my hands, thighs pressed against the sides and feet pushing on the pegs, I was fully in the present, in the now. My muscle memory returned and my stroke miraculously improved. Using my emotional and physical core, I shifted our direction, turning alongside the waves. Water sloshed over the spray skirt, but we stayed upright. Paddling with renewed determination, I pointed Greenie in the direction of the distant landing. The waves rose from behind. The urge to tense was strong, but focusing on my breath helped me relax into a different kind of control.

“When going with the waves,” my teacher had said, “find the rhythm and put the paddle into the crest of the wave as it emerges from beneath the kayak.” I turned off the scary movies in my head and got attuned to the lifting swells. As I regained access to al of my senses, I found the connection I needed between water, boat and body. My eyes no longer needed to identify each rising, threatening wave. Instead, I could use my sight to determine where to more correctly place my paddle and hold steady to the point on the horizon where Greenie and I would eventually land.

That evening, on the porch overlooking the lake, we saw a hue-drenched double rainbow. Bill took my hand as we stared at the magical arc of colors. “That was the most fun I ever had kayaking,” he said, turning towards me, excitement glinting in gray-green eyes. I hesitated, looking up at his dear, enthusiastic, expectant face.

It matters how we tell the story. What to say? Already the moment was part of my past. No longer in the present, the series of thoughts, feelings and actions were already coalescing into anecdote. Could I avoid judging what happened as “the worst” or “the greatest?” Could I have compassion for myself and how I reacted, not add more evidence to the belief that I was “helpless and incompetent”? What could I learn by being curious about my inner experience? In my mind, the tale ends with an image of the double rainbow, the ancient symbol of renewed hope after a storm. I kissed him and we gazed out towards the horizon.

Our adventure on that stormy lake taught me that I have a choice in how I meet life’s events—especially the ones that threaten to swamp my metaphorical boat. Looking back, I could recognize that attachments to old, shame-ridden identities, whether self-imposed or laid upon my self-image by the judgment of others, were interfering with what in this case was a life-saving moment. Whether life’s challenges are physical or emotional, we can unburden ourselves of toxic, unhelpful self-beliefs and use what is brave and strong within us. What part will we choose to play in the movie in our mind? The hero, the villain or the victim?